Water Report

Water is once again visible and integral to the life of the district.

Over the last years the district has often been referred to as “lush”, which is not a common descriptor for a residential zone so close to the centre of a city. That impression probably derives from our highly visible agriculture, but it also reflects the role that water plays in our environment. Even in these dry and hot times, one encounters water and water systems everywhere across the district.

Water has always been important in the history of this site. Before European settlement this was a network of swamps, lagoons and marshes; an important part of the local ecology of Melbourne, rich in life (birds, frogs and fish). The area was part of what became known as Batman’s Swamp. The land was also important in the Wurundjeri aboriginal culture .

For the local Wurundjeri tribes, the system of Yarra billabongs which kept the river healthy, formed a cluster of riverside sacred sites, and were the defining elements of Kulin Woirurung land. Ley Lines, Sharon Thorne

The history and natural ecology was important in the early development of EBD. Before any building took place the site underwent a remediation process; some of this was through phytoremediation as well as other more industrial methods. After remediation the surrounding natural ecosystems have gradually been restored. Not only have the wetland systems reappeared, but through clever landscape design these wetlands clean the water in Moonee Ponds Creek and are an integral part in EBD’s water recycling systems. The natural systems are supported by sophisticated technology systems which monitor and communicate the health of EBD water. The visible technology of these systems is a focus for so many educational programs. We have a unique aesthetic reflecting a celebratory approach to water. Moonee Ponds Creek is a focus of these systems, as the creek enters the site to connect with the EBD lagoon and wetland systems. The creek water is now cleaner than any time in the last 50 yrs and net flows have been increased with additional water from the site. We send millions of litres of improved water to Victoria Lake, which is a city reservoir is used by the Melbourne City Council as part of its catchment system. Water Gates are the barrier to unexpected contamination; in an emergency they will divert water to a special containment trap and then to the city’s storm water system.

EBD is very close to sea level and the threat posed by sea-level rise has been critical to its design-development. Using unique landscape interventions we have successfully managed the water entering the site during storm surges. The barrage at Victoria Lake also protects EBD from creeping sea inundation.

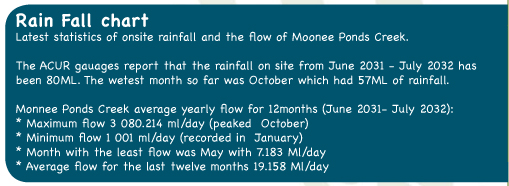

EBD harvests 100% of on-site rainfall. Rainwater, along with recycled water, keeps our veggie gardens and street trees (fruit and nuts) lush and our residential bathrooms and laundries operating. We are (as everyone knows) disconnected from the Melbourne sewer system (remember the debates about this radical idea in the early days of the site planning) with our own recycling and water treatment-reuse systems. Sewage ‘separation’ was initially posed as a stimulation for innovation rather than a way of reducing infrastructure investment. Rather than ‘sewer-mine’ (withdrawing water from the main sewer trunk), as many buildings did during the early years of the century, the proposal was to develop a local sewer system that conserved water and allowed recycling of water and human waste. We have a sophisticated water system recycling and treating wastewater from the district, and of course there is our separate urine system which provides treated nutrient for horticulture. The emergency connection to the sewer which was installed as a safety back-up has never been needed. Our model of treatment and reuse is now widely adopted for new developments. Many new services and products of EBD businesses which are exported from Victoria owe their existence to this ‘stretch challenge’.