Melbourne School of Design graduates: Danielle Mileo

Danielle Mileo is a recent graduate of the 300-point Master of Architecture program, which is for students who have studied a prior degree outside the built environment disciplines (career changers), at Melbourne School of Design (MSD). She is an artist and aspiring architect, and travelled to New Zealand in 2016 to install her thesis as part of FESTA – the Festival of Transitional Architecture.

Can you tell us about your background? How did you end up at MSD?

My background isn’t actually in architecture. I completed my undergraduate degree in fine art, majoring in sculpture and spatial practice at the VCA (Victorian College of the Arts) in 2011. In my second year of art school I was on holiday in Japan and it was there, standing in front of Bruce Nauman’s 100 Live and Die (1984) that I discovered architecture. Nauman is probably one of the most important conceptual artists of the 20th century, and I absolutely adore his work, but it was the room* around it that totally captivated me – this vast, cylindrical volume that was all consuming and yet entirely appropriate and sensitive to the art it housed. I thought to myself, ‘I’m working on the wrong scale.’

Almost immediately I started research into architecture education, and found this fascinating new course at the MSD, the 300-point program – a masters program for people who’d studied something other than architecture during their undergraduate degree. MSD was the only school in Australia that offered a course with such a diverse and exciting student body, and that was really intriguing for me. I set about doing the prerequisites, applied and started it in 2012.

Tell us about your thesis project?

My thesis project examined the erasure of key touchstones in the collective memory of Christchurch in the wake of the Canterbury earthquakes. It’s a three-part project that uses parallel processes in research, exhibition and speculation to explore the implications of lost Heritage architecture and memory in the city.

The first part of the project was a research task that mapped the vast erasure of Heritage architecture in Christchurch. This loss has left an immeasurable impact on the built environment, as Heritage-listed buildings have been lost through a rapid demolition process with little to no regard for the input of relevant Heritage authorities. This process has fundamentally altered the physical presence of the collective historical past and reshaped the identity of the city. Since the earthquakes, 136 Heritage-listed buildings have been erased in central Christchurch alone. My work involved the examination of the 70 Heritage-listed buildings that were lost due to the earthquakes and collating that research into an archival volume that tracks both tangible and intangible loss.

Part two of the thesis project engages in art practice and spatial installation as a way to exhibit the information collated in part one. I traveled to Christchurch to install my work as part of FESTA – the Festival of Transitional Architecture – a biennial event in Christchurch that celebrates urban creativity and renewal in the wake of the Canterbury earthquakes. The aim of my installation was multifaceted: to highlight the loss of cultural heritage, to stress the value of remaining Heritage architecture, to present new information to the community, and to prompt viewers to consider what this loss means for them and for the future of Christchurch.

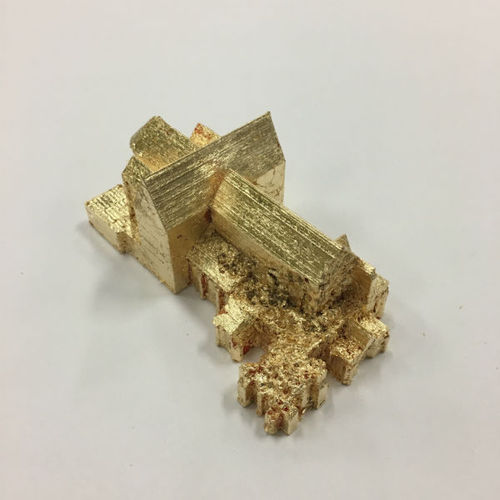

The third part of the project is a speculative architectural intervention into the site of the Christchurch Cathedral, the most contested Heritage site in the city. It proposes a new world monument for Christchurch at the centre of the city that functions as a repository, memorial and a civic space. The speculation also provokes us to pause and take stock of the post-reconstruction blueprint, five years after it was first conceived. The work is both a physical expression of my research and a reaction to the current state of memorialisation in Christchurch, and was presented in my final critique when I returned from FESTA.

What inspired you to take on this particular project? How did it eventuate that you would be completing this project in NZ?

I spent a year in Japan between 2014 and 2015 studying post-disaster reconstruction and looking at the role of architects in post-disaster landscapes. While there, I became interested in the role of architecture in preserving or altering memory on a civic scale and decided to investigate this further for my thesis project.

When my supervisor Professor Alan Pert (Director of the Melbourne School of Design) and I were discussing potential sites for my project, Christchurch came up as a city undergoing a process of physical change. I applied to be part of FESTA and, once accepted, booked a site visit for week one of this semester. In Christchurch I learned more about the loss of Heritage architecture and the rigidity with which the new ‘blueprint’ for the city was being implemented. My experiences in Japan had taught me that these kinds of events are always marred with difficult politics, but the blank canvas approach to rebuilding in Christchurch really shocked me and became my impetus for highlighting what has been lost through that rebuild process.

What have been some of the biggest challenges and rewards of the project so far?

As my thesis is broken into three parallel projects that inform each other, the biggest challenge has been communicating this as a body of work, rather than just a singular architectural outcome, so I’ve been focusing on how to embed my research and experience into the architecture. The biggest reward so far has been receiving a call from the director of FESTA, Jessica Halliday, saying that she was really happy with, and touched by, my research into the lost Heritage architecture of Christchurch. The loss of Heritage architecture had yet to be mapped out collectively in this way, and she was so appreciative of my research and output. It’s a really incredible feeling to know that your work as a student can contribute to something bigger.

What made you choose MSD over other schools that offer architecture programs?

MSD is such an incredible platform for learning. It’s currently the only school in Australia to accept non-architecture graduates into its masters program, which means the student body is really diverse. It’s also a relatively large school and, as a result, offers students a plethora of opportunities to learn across a range of contexts, disciplines and media. We have a constant flow of international and local industry professionals and academics coming to speak, lead workshops or visit our studio classes, as well as an amazing event calendar of exhibitions and lectures. I really can’t imagine studying anywhere else!

Which subjects or areas of the course have you found most valuable and why?

It’s hard to pinpoint one subject that is most valuable because I’ve had so many wonderful experiences during my time here. I think the best thing has been the ability to structure the course around my interests – I’ve done a travelling studio, been on exchange, participated in international competitions, learned about curation, put on exhibitions and participated in workshops with world-leading architects. For me, it’s not the specific subject, but the abundance of opportunities that MSD provides you with to tailor your studies to suit your interests and learning style. I’ve also been lucky to have had a host of dedicated and passionate staff teach me throughout my years at MSD, many of whom have gone on to become mentors.

What are you looking at pursuing once you graduate from the program?

Ultimately, I’d love to start my own practice that interweaves art, architecture, curation, design and research, but first I’ll be taking a little bit of time off to travel and reflect on the past few years. I’m spending time on collaborative projects with some of my peers while working in architecture.

What advice would you give to future students who are thinking of studying architecture, or future students who are thinking of taking a career change into architecture?

Do what you love – I know that sounds cheesy, but it’s something that has driven nearly every decision I’ve made regarding my studies and career. Changing from one discipline to another only makes you a more compelling and interesting person, and allows you to see the world from multiple points of view, so don’t worry about trying to be linear or taking a ‘normal’ career path.