Yaseera Moosa

Modern urban form is contingent on invisible utility infrastructure located in what Timothy Morton describes as the mythical land of Away. For Melbourne, one such place is the Latrobe Valley, where nearly all our energy is produced and supplied in uninterrupted excess. Much of this energy is wasted. And the wastes of production are rendered invisible via distance.

Parallel to this, is the subterranean world of sewerage. We have many names for urban water: rainwater, stormwater, grey water, black water. All of it is drained. From the sewers underfoot, water is pumped an hour out of the city where it is treated and then drained into the ocean, effectively wasted.

The sewers are the backbone of the city. They are inexorably connected to urbanization, sprawl, and consumption. With the introduction of this subterranean urban landscape, connections between distant sources of water in remote areas and the metropolis completely changed our concepts of space and time, expanding the city’s limits infinitely underground, permanently modifying the landscape.

Our sewerage system is not only wasteful in its delivery, but in the architecture, it has enabled, through the proliferation and privatization of wet areas, which are both inefficient and antisocial.

Prior to the introduction of drainage, human excrement, euphemistically referred to as “night soil” was used as fertiliser in a working agrarian economy. Sanitary infrastructure and industrialisation have fragmented systems of exchange, creating a false dichotomy of “resource” and “waste.

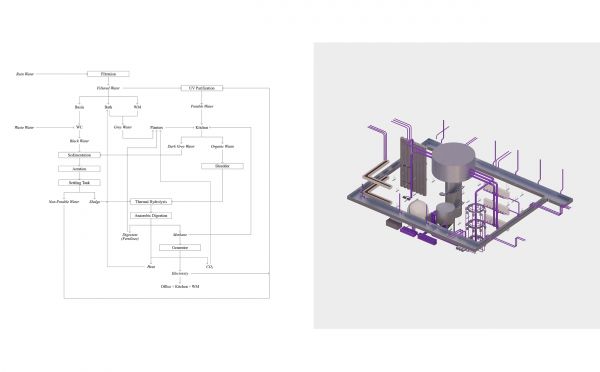

In response to the inefficiency and invisibility of our water and energy systems, the project is conceived as a local act of resistance that is both collective and decentralised. It is a replicable strategy at the scale of the city block. A potential network of wet utility, combined with water treatment and energy production.

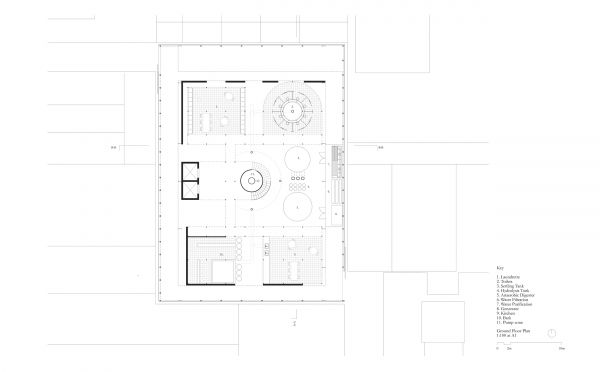

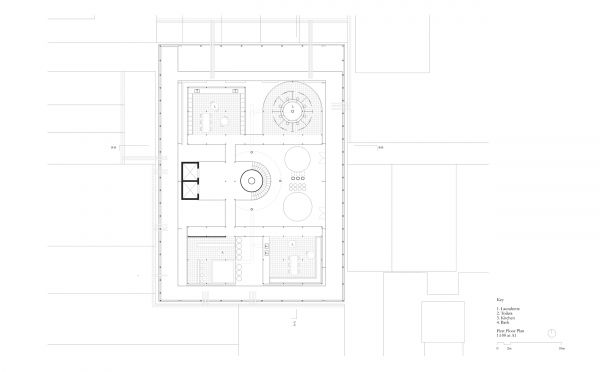

Alongside the system, the project seeks to respond to the paradox of increased densification and isolation. As our cities become more populated, our living conditions have become more cramped, as we squeeze the entirety of our lives into singular, segregated boxes. The project offers the “wet area” as a civic space of shared luxury, offering both social and hydrological utility. It is composed of four wet areas, the toilet, bath, laundry, and kitchen.

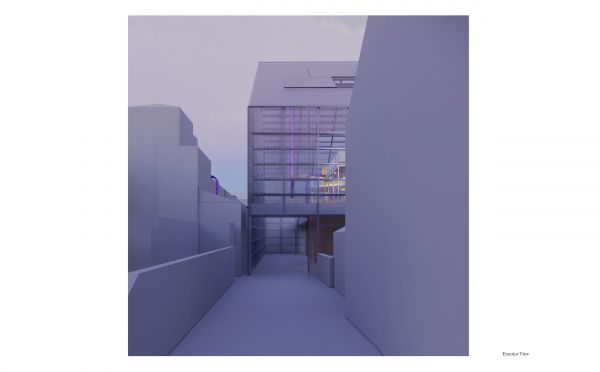

Located at the rear of all its neighbours, the site serves as a common backyard and laneway for the block. It echoes the historic use of laneways as passages for night soil collection connected to the wet work of backyards, lively with laundry, productive gardens, and conversations over the fence.

The average Australian uses about 200 Litres of water per day. In Melbourne, the amount of rainfall received exceeds the city’s water usage, yet rainfall collection in urban areas remains rare and meagre.

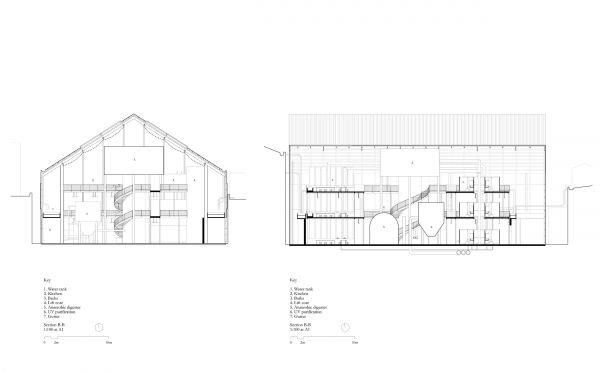

In contrast to this, the building is conceived as a giant container. A sponge rather than a skin. The roof covers the full extent of the site, maximising collection. A parasitic network of downpipes collects rainwater from adjacent roofs, rescuing it from the condemned destiny of “storm water”. The shell of the building is operable so that the space can be externalised during dry weather and sheltered when it is wet or cold.

Upon collection, water is filtered, purified via an internal gutter. It is then pumped up to central water tower to be gravity fed throughout the building. Grey water is used to flush toilets, water plants or washed back into the gutter for re-treatment. Black water is separated and treated to produce clean water and sludge. Sludge, combined with kitchen food waste is fed to an anaerobic digester to produce heat and biogas for electricity. The building can hold 500 000 Litres of water at any given time and would be replenished frequently given Melbourne’s abundant rainfall. This amount accounts for 357 individual’s weekly water usage, a number which rapidly increases as water is recycled. In a month without rain, it could provide first-use water for 83 people and recycled water for 416 people. Excess water could be supplied to adjacent parkland, along with fertiliser produced during the anaerobic digestion process.

The system forms the centre, perimeter, and shell of the building, rendering the interrelationship between collection, use and process and constantly apparent. The gutter and toilet block, central to the building’s operation, are celebrated and exaggerated. In the familiar style of “home office”, workspaces are distributed throughout the kitchen and laundry, rejecting the hierarchy and segregation of work, non-work, and housework, nudging at the fallacy of common distinctions between usefulness and waste.

Presentation

Folio