Romaldo Giurgola: our tribute

We farewell one of our great architects, Romaldo Giurgola.

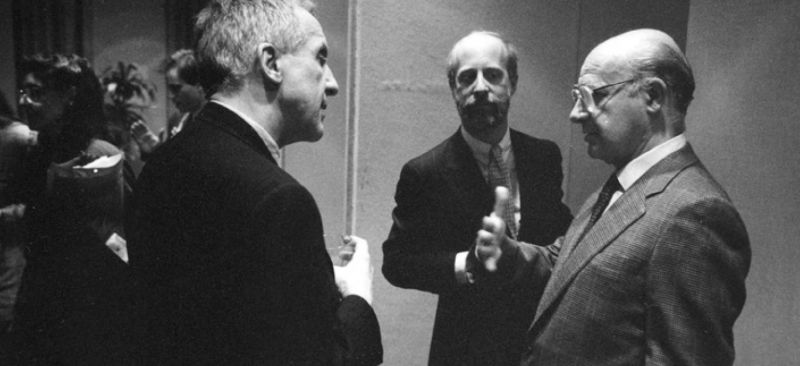

Picture: Kenneth Frampton, Paul Goldberger and Romaldo Giurgola, New York, 1990. Image courtesy of Prof Paolo Tombesi, Dr Annmarie Brennan and Prof Philip Goad.

UPDATE: Monday 30 May, 2016

As the Faculty mourns the passing of Romaldo Giurgola, many of us have reflected personally on this loss. Dr Jeff Turnbull has written a personal note:

The great Australian architect, Romaldo Giurgola died earlier this month, aged 95. Romaldo was Italian by birth, studied in Rome, then moved to Philadelphia USA in the 1950s. He founded in New York the firm of Mitchell/Giurgola. Mitchell Giurgola and Thorp won the International/Australian competition for the design of the new Parliament House in Canberra. He moved to Canberra during the 1980s and completed the House in 1988. Giurgola remained in Australia and completed many outstanding commissions, including the architecture studies building at UNSW and Paramatta Cathedral. He became an Australian citizen in 2000.

Romaldo gave great support to the Master of Architecture by Design programme here at the University of Melbourne during its short existence, frequently coming to Melbourne to give the students illustrated talks and workshop design projects. These often focussed upon appropriate additions to the Griffins' Newman College Initial Structure. Around that time, Romaldo was made an adjunct Professor in our Faculty.

In the late 1960s, Robert AM Stern produced a book for Studio Vista on new directions in American architecture. Stern featured the promising works of Giurgola, Robert Venturi, and Charles Moore (all students of Louis Kahn) as setting a new direction for American architecture. Later, Charles Jencks featured the same three architects as 'pioneers' of 'Postmodern' architecture.

Charles Moore commented that he would prefer to be called 'Presomething' rather than 'Postsomethingelse'. Asked to write a review of Charles Jencks' book, 'The Language of Postmodern Architecture', Charles Moore wrote: "At dinner the other night in my local restaurant, the people at the next table discussed lead futures rather than gold. This reminded me of the mad alchemist, Charles Jencks, concocting out of the rancid remains of the Modern Movement, and the bleached bones of its predecessors, a new and vital amalgam".

Romaldo believed that new work should be cognisant of the Order of the Land, and the Order of the City; that a new work was inevitably composed within the knowable landscape and urban contexts.

Romaldo's death is sad, and hopefully the Faculty can reflect on our brief and fruitful relationship with this outstanding person.

Tuesday 17 May, 2016

Today we send our heartfelt condolences to the family, friends and colleagues of Romaldo 'Aldo' Giurgola. His passing last night represents the end of an era for architectural culture. We present a personal recollection from close friend and colleague Kenneth Frampton, which he wrote as an introduction to 'The Reluctant Master'. This symposium celebrated Aldo Giurgola's 90th birthday at the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning and took place in 2011.

Aldo and Kenneth: Recollections of a friendship

Kenneth Frampton

Ware Professor of Architecture

Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

Columbia University

Modest master-architects are a relatively rare breed even though they surely exist as the long and productive career of Romaldo Giurgola amply testifies. From our intermittent relationship for over forty years, which by now is already half my lifetime, I have in my memory a number of momentous mutual incidents, such as that occasion when I showed up on your doorstep soon after you became Chairman of the School of Architecture at Columbia, when you welcomed me warmly and were on the verge of offering me a job, before the chain-smoking, ash-blowing engineer Dean Kenneth Smith brusquely informed you that there was no budget line available that could permit me to join the faculty. Later, after James Stewart Polshek became Dean, there were those many years at Columbia when you were my ever generous, supportive and soft spoken colleague, and when your self-effacing, accented charm was totally at variance with your exceptional talent both as an architect and a superbly gifted draughtsman.

Your unique entry for the Boston City Hall, with which I first became acquainted, when I was still the technical editor of the British magazine Architectural Design, is how I first became aware of your prowess as an architect of public buildings, which you would demonstrate repeatedly over your long American career, even if the tectonic rigor of that particular design would become mellowed over time by the more conciliatory empirical ethos of the Philadelphia School. When I look back over your career I am still surprised by the variability of your manner, the way in which your work would be subtly varied according to the program and the topographic context. I have in mind the way in which your finest work invariably depended on the inflection of a received typology irrespective of whether this was the stepped and chevron organic form of the student dormitory at Williams College, Massachusetts (1972) or the classic prismatic four square plan of the Music Building at Swarthmore College (1978). Otherwise, it could be said that, like Louis Kahn, by whom you were evidently influenced, you were quintessentially a brick architect, first arriving at your mature manner with the Foundation Hall at Bryn Mawr, in Pennsylvania (1972), surely touched, in its turn, by James Stirling’s Florey Building, Oxford (1968) and going on to the sweeping magisterial form of your Aaltoesque Lukens Steel Co. Headquarters in Coatsville, Pennsylvania (1979).

It was around this time, I believe, that you first began to work for Volvo, beginning with that company’s Chesapeake plant in Virginia (1976); the first of its kind in the United States. And this brings me to that moment when you inadvertently had a decisive impact on my overall outlook by virtue of inviting in 1973 the then director of Volvo, Peyr Gyllenhammer, to speak to the students and staff of the school at Columbia. Gyllenhammer’s address had an immediate impact on me, to such an extent that when I returned to the UK in 1974 to teach at the Royal College of Art I immediately paid a visit to the Volvo experimental plant at Kalmar in Sweden. I was so overwhelmed by this ingenious, cybernetic attempt to overcome the alienating nature of repetitive on-line automobile production that I would devote a long essay to Volvo’s Kalmar and Skövde plants for a special issue of the Italian magazine Lotus. It was also you, with your Scandinavian affinities, who would introduce me to the Danish ceramicist Lin Utzon with whom you collaborated on a number of occasions and who I would later invite to lecture in the school.

In 1983, some five years after my return to the States, I wrote an appraisal of your work up to the moment of your winning the Australian Parliament House competition in 1980, with a truly remarkable entry designed in New York with the Australian architect Richard Thorp, on the basis of which the firm of MGT was founded in Sydney in the following year. On this occasion somewhat less than thirty years ago, I wrote:

The strength of Giurgola’s design can only be finally appreciated on the site itself where the building assumes the status of an artificial acropolis and where the colossal elliptical concrete berms draw the all but invisible geometry of Griffin’s City Beautiful plan into three dimensional relief.

It is embarrassing to have to admit in retrospect that at the time I wrote these knowing words the building had yet to come into being and I, for one, had never visited Canberra. And in fact, as you know, only too well, I would not finally, fully experience this compelling and moving work on its remarkable site until some six years later when you showed me over, every square inch of the complex, in the company of two distinguished Spanish architects, Oriol Bohigas and the late Pérez Pita, both of whom happened to be in Canberra at the time. On that occasion you were so considerate as to arrange for me to stay overnight in the mythic Robin Boyd house, hidden away in the suburbs of Canberra.

What more can I say to you when all these fragmentary strands from the past rise and fall across my consciousness? What can I say to make up for my untoward absence on the occasion of this academic celebration of your work and life, as one Ware Professor to another? There is surely nothing more to say except to raise my glass, on the other side of the world, in order to drink to your health and to thank you for everything you have given us.

New York, August, 2011