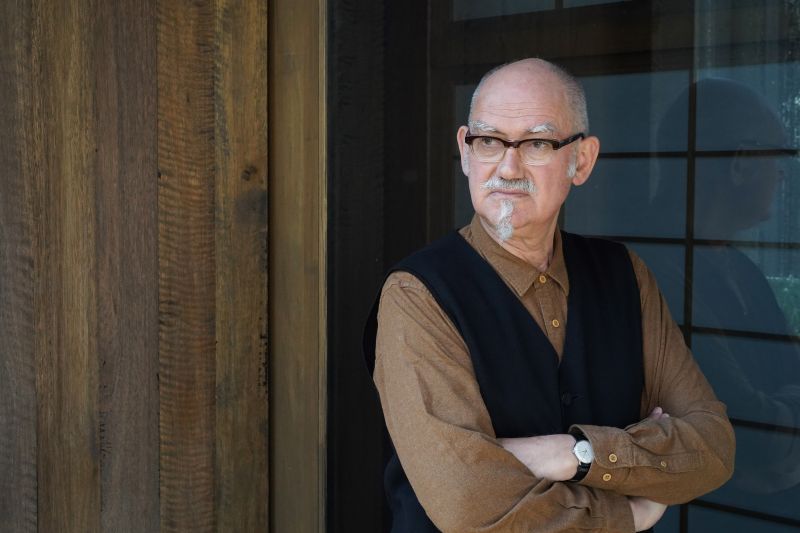

In Conversation with Peter Wilson

Australian-born Peter Wilson co-founded the architecture firm Bolles + Wilson, with Julia Bolles in 1980. Having won the Australian Institute of Architects (AIA) Presidents Prize in 2009 and the AIA Gold Medal in 2013, Peter Wilson recently returned to Australia to receive an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Melbourne, and to deliver the BE-150 Dulux Dean’s Lecture presentation at the Melbourne School of Design.

You were born in Melbourne, but have spent most of your adult life in Germany. Do you still feel linked to Melbourne, and would you like to build here one day?

I would love to build here. It would in a way round off my life cycle, it may end up being a mausoleum. I have a curious relationship with Melbourne; nostalgic in a way, I still know my way around the streets, even though it's been nearly 50 years since I left.

Something curious is that the circle of people now in the Melbourne architecture world are the same names that I was familiar with when I left. They were young turks then, and now they're the leaders of the profession. It seems like the whole scene has just sort of moved up. As a 20-year-old student, I didn't really have any access to this scene. Now it's quite gratifying when they all come up to shake my hand.

Which part of Melbourne did you grow up in?

In the eastern suburbs, the Wheelers Hill area. It was outside the suburbs then, and we thought of ourselves as living in the countryside. I had a horse and used to go riding in the small leftover pockets of forest.

Then from the other side of the hill a kind of a suburban tsunami, a wave of housing came and swamped everything. But when I was growing up, it was all market gardens and the ruins of the first wave of settlement. There were abandoned old wooden houses. My parents bought one and encased it in brick. It was an ideal place to grow up, but somewhat off the map. One had no connection to any urban world, or any social milieu apart from a few neighbours. My childhood was characterized by a disconcerting sense that there must somewhere be an elsewhere.

Did you feel like you were missing out on that “elsewhere”?

I think so. That's probably what drove me overseas. When I arrived in London, it was like I had left the periphery, and arrived at the epicentre of everything. It was incredibly exciting. I landed at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA), and back then the AA really was the avant guarde of architecture.

In your Dean’s Lecture, you spoke about cities in Germany that have begun to sprawl into each other. What are your thoughts on this phenomenon?

I think it's a regrettable evolution, but one that we that can’t afford to ignore. Official German planners try to ignore it by still talking about the city as an isolated entity, with the countryside as beautiful green outside. But in reality, it's not like that anymore.

We have been researching what triggers this European phenomenon: the freeway network now equally accesses the entire landscape, you can get to any place on the map 'just-in-time'. And in any case with new media, proximity is of secondary importance. Conferencing is possible wherever one is located. Basically, technologies have emerged that makes the focussed city redundant.

Such network fields seem not to evolve in Australia, maybe because distances are much greater. CBD towers are instead engulfed by unsustainable and endless sprawl.

In Europe this curious phenomenon which we term the Eurolandschaft is ubiquitous. Rem calls it Junk City, the Italians call it la città diffusa; the diffused city. Around Milan and across the Po Valley it has reached monstrous proportions, an endless sequence of places with absolutely no character.

On the other hand, to understand this new settlement pattern requires developing a whole new spatial sensibility. Like the films of Wim Wenders, filmed out of a car window unselectively panning everything that comes. This implies that everything you see is of equal value, with no inherited aesthetic hierarchies in play, my experience and conclusion from this mode of perception is the emergence of a filmic and highly poetic urban melancholy. I started writing about the Eurolandschaft because we were regularly traveling by train across this junk terrain. From the train window one pans the matrix of urban conditions: ruined or functioning industry, power stations, big boxes, an office complex, a biotope, etcetera. A not entirely uninteresting menu.

As an architect, one is only empowered to intervene at individual points on the map (monads). Whereas a planner could in theory be more effective in rescripting the whole carpet, but planning plays a rear-guardegame using outdated tools. Eurolandschaft husbandry requires elastic systems and an understanding of circuitry. Keller Easterling writes profoundly about the American version of the networked landscape. She has developed a new and enlightening vocabulary for describing circuitry, how physical and ephemeral systems overlap.

Münster City Library, completed 1993. Image by Bolles + Wilson

People generally identify the winning of the Münster City Library competition as the turning point for Bolles + Wilson. Do you agree?

Our theoretical researches before the Münster City Library were absolutely essential to our subsequent engagement with practice. But I do agree it marked a phase transition. It was such a revelation to actually be building a substantial public building, to be dealing with materiality, and to experience the realising of a building in every last detail, this was what we had been rehearsing for years.

Teaching at the AA for me was like a protracted postgraduate education. Basically, we spent a long time developing a vocabulary of forms that subsequently surfaced in our built work.

Also, it was essential for us to leave England. We never would have made a breakthrough like the Münster Library in England.

Why do you think you wouldn’t have made a breakthrough if you had stayed in England?

In London, the property market is so over-heated, that only the big commercial firms ever get a foot in the door. Even people like David Chipperfield never really got started in London, building first in Japan and elsewhere before being recognized at home. All of us at that time did interiors, shops, furniture and things, but to move from that to a free-standing building was almost impossible.

Is this still the case today?

I don’t know the current English scene that well. Hopefully when young practices do good work, they do get picked up.

But I’m very cynical about the way the building industry is structured in England. They have a labyrinthine planning system, requiring reports 15 centimetres high, and then somebody else writes a report on the report. Basically, there’s so much money floating around in building, that all sorts of peripheral fields have smelt the chance to get a slice of the cake.

English planners have evolved a planning system that demands ‘best practice', and a load of other terminology which means absolutely nothing, because you cannot quantify quality. Planners write long, long lists using all the right words, ticking all the right boxes. It’s a sort of legalized blackmail that the poor clients have to go through to get planning consent, all at great expense. I was quite pleased not to have made a career in that environment, and to be in Germany. Germans are very factual, they are goal oriented, intent on taking the shortest path to get the building realized.

We had a sort of special status in Germany when we moved there. We were wild cards, because what we designed was radically different to what everybody else was doing. They still regard us with a certain suspicion. Our architecture is considered to be on the verge of chaos, and chaos is the absolute worst word you can use in Germany. They have the word 'Ordnung', which means Order. There even exists a city department for order, the Ordnungsamt.

What do you consider your stand-out project at Bolles + Wilson?

I really like the Suzuki House in Tokyo. The Münster City Library obviously was also a stand-out, but the Suzuki House remains a yardstick for us. We've built a lot of other small, characterful objects but that was the first. It was very much like a realization of the theoretical project type I was producing while teaching at the AA.

I also have a soft spot for our latest, the National Library of Luxembourg. And for the recent Albanian work we’ve been involved in, it’s wacky and really loose fit.There, our Masterplan strategy is never complete, but introduces a set of principles to fall back on when new questions or new jobs emerge.

The Albanians keep reeling me in. In Korça they have given me the title 'City Architect'. Whenever they have a new building, they get in touch or, quite often, I think up a building and say "couldn't you do that here?". That's how the Sports Hall inside a ruined Communist structure, that I showed in my Dean's Lecture, came about.

The Albanian projects have gone so well now that we're talking to a German Development Bank about how they might invest 60 million Euros in development in Albania. They are asking us which projects they should prioritize. It's really quite gratifying to be at the forefront and influencing how a country develops.

The Suzuki House, completed 1993. Image by Bolles + Wilson

Thinking about the Suzuki House and the work in Albania, they seem almost like polar opposites in terms of project type. How do you see them?

In organisational systems, they were similar. In both cases we were working from a distance, which requires a local architect to be on the ground and to interpret our concepts. With the Suzuki House, there was a long dialogue with Akira Suzuki, he and I faxed back and forward when faxes were hot technology.

I'm really pleased that the Suzuki House has also become a sort of international yardstick. Their daughter who grew up in the house now lives in London. Recently, we arranged to meet her because we wanted to see if she had any psychological damage from growing up in a 2 x 2.5 m concrete box kids' room. She turned out to be a really nice girl. The Suzuki House has this black blob on the façade, which we have a long architect's conceptual explanation for. I asked her how she, when growing up, explained it to her Japanese schoolgirl friends. She said, "Oh, that's easy, I told them my house was a Panda Bear." This is great, we architects talk about narrative, but she'd invented her own story.

In your Dean’s Lecture, you showed some of your own personal sketches.

I don't usually show those. That was almost their first outing. In a conventional sense, they are not architecture. But for me such work is essential research, a rehearsal for engagement in more conventional architectural procedures.

A lot of the focus now in architecture is on digital software and digital design. What do you think about the way technology is influencing the profession, and the way students are taught?

There is a conversation people of my generation have, an old fogey conversation. We all talk about how great it was when we drew by hand, and how the kids have lost it. There certainly has been a fundamental shift in the mode of production in architecture, which is in some ways worrying.

I have a neurologist friend who claims that when one draws with one’s hand, a different part of the brain is activated; different, that is, to the part of the brain activated when working on a computer. The hand drawing activates the creative side of your brain. There is also the problem that working on a computer, requires speaking two languages simultaneously. First, the language of the computer where absolute fluency is required for the language to be transparent. And in parallel, one is trying to be creative with architecture, a whole other language to master - a monumental task and juggling act. There are certainly new modes of composition derived from digital procedures, but to be able to abstract this requires a quite sophisticated critique. One that is not always available to students. A breadth of knowledge is essential to the production and refinement of architecture.

I am convinced that hand drawing is intuitive. It activates the body as the principle design tool.

'The Water House' drawing by Peter Wilson

Is it a similar philosophy behind the fact that Bolles + Wilson use a lot of wooden models as part of the design process?Yes. It's the physical, the haptic. Something that you can touch, and hold in your hand, a mind/brain connection.

So, for Bolles + Wilson, that physicality makes a big difference in the creative process?

I think so. We are actually very undemocratic about the creative process. It's quite difficult to get the younger kids in the office up to speed to be able to come up with things as quickly as an old fox like me. I can take problems away, come back two minutes later with a hand drawn sketch, and that's it, problem solved. They simply can't work at that speed. There is something 'loose-fit' about the hand drawing, like floppy logic. If you work digitally, you're working with an absolute precision, down to the last millimetre, and that can be a stumbling block when working with elastic concepts.

One of the major projects that you're working on at the moment and is nearly completed is the National Library in Luxembourg. Do you know what's on the horizon after that?

No, it's a big black hole. We are working on smaller projects in Albania. And we're constantly doing competitions. We are, in fact, totally dependent on competition wins as our principle mode of acquisition.

Bolles + Wilson have been extremely successful at winning competitions. Why is that?

It's to do with our location. In Germany there’s a law that every public building has to go out to competition, so there are lots of competitions. It used to be that young architects could get into the profession that way, when it did not take an excessive amount of effort to do a competition by hand. These days, to enter a competition costs us internally €30,000. It's a major commitment. This evolution has led to a sort of standardized product expected by the jury. And the competition result is only as good as the jury; good jurors are necessary for a good result.

If you have lots of little competitions for every kindergarten and every school, it means that the good jurors are spread very thin. Mediocre jurors are actually frightened if they see something original, so they only choose what they know, which means things get slowly more and more conventionalized. Our competition success rate has gone down rapidly in recent years. Julia says we've gone out of fashion, but I think it's the quality of jurors that's to blame.

Korça City Centre Masterplan. Image by Bolles + Wilson

You have an international reputation as an architect, but you are also recognized for your role in architectural education. How did that come about?

When I graduated from the AA, I stayed on as an assistant to my teacher, Elia Zenghelis and then to Rem Koolhaas once he returned from America where he had been writing Delirious New York.

Being in London was like being at the epicentre. Zaha Hadid was a student of our unit at that time too. It was like being there at the Big Bang when the world started.

Later I had a professorship in Berlin for two years shortly after the Wall came down. That was really interesting, because the school was in the former East Berlin. I was the follow-up professor to Daniel Libeskind, who didn't show up. My students were 50% from the East, and 50% from the West. All really nice kids, equally talented. But after a while, one noticed a really big difference. Halfway through the term, the kids from the East sort of sat back and didn't do very much, because they'd grown up in a system where the state did everything for them. They were looked after their whole life.

Meanwhile, the kids from the West suddenly started working really hard and doing really good work. My interpretation of that was that we, from a capitalist background, are extremely aggressive animals. We elbow ourselves forward. That was quite a revelation.

Teaching is exhausting, to be honest, because my way of teaching is not to teach a theory or a system, I discuss individually with each student to incubate their individual personality. So, there is a maximum number of students one can teach.

My teaching technique is basically based on how I taught at the AA. I was a unit master there for 15 years. I stopped teaching because my wife Julia became professor and then Dean of the school in Münster (MSA) where we're based. One of us had to stay in the office, so she's the one who has recently taught the most. Though, we did teach together in Winter Schools in Havana.

Peter Wilson visited the Melbourne School of Design as part of the 2019 Dean’s Lecture Series. View Peter Wilson’s BE - 150 Dulux Dean’s Lecture here.